Open The Floodgates!

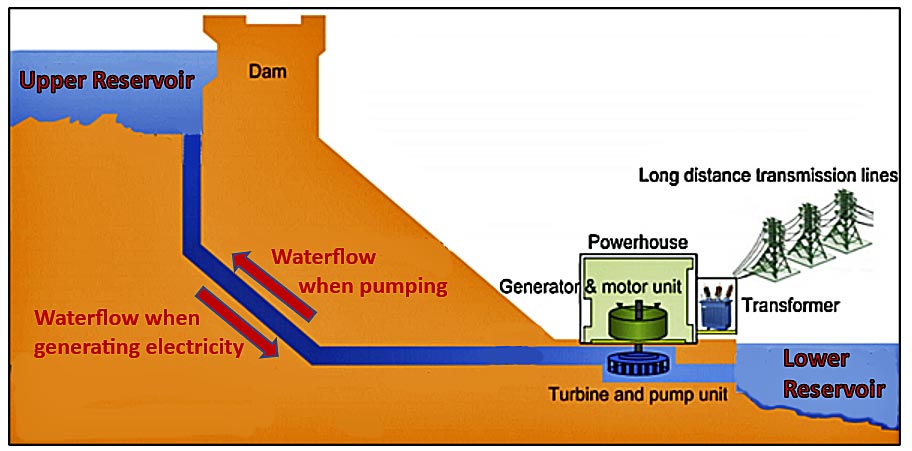

Hydropower was the original clean, renewable energy source. It remains vitally important today. It is mandatory that the electricity grid provide enough electricity to meet total demand reliably—24 hours a day every day of the year. As we switch to renewable energy sources such as solar and wind to meet climate change goals, grid reliability becomes a major issue. That is where hydropower comes into play. Hydropower acts as a water battery. When the sun isn’t shining or winds aren’t blowing, hydropower can be turned on in seconds or minutes to contribute electricity to balance the grid. It serves as a force multiplier, enabling greater amounts of variable wind and solar on the grid.

A comprehensive 2016 Department of Energy study concluded that combined US hydroelectric generating and storage capacity could be grown 50 percent by 2050, with 25 percent of the growth coming from new hydropower generation capacity (upgrades to existing plants, adding power to existing non-powered dams and canals, and limited development of presently undeveloped sites) and with 75 percent of the growth from new pumped storage capacity.

Permitting remains a huge issue in maintaining the existing hydropower fleet and in adding needed hydropower capacity. Up to 11 federal agencies may participate in the hydropower licensing process. In addition, the participation of state water quality and wildlife resource agencies with jurisdiction as well as tribal and public engagement is required. Renewing a license can take 10 years or more and 10 million dollars or more—and over half of renewed licenses require some construction activity. Obtaining a license for a new facility on average takes about 2 ½ years less time.

The complexity of the licensing process and the time it takes are frustrating to all involved. State water quality certifications, Endangered Species Act certifications, and the extent of required public participation especially can drag out the licensing process. It should be noted that facility owners who have not yet received a relicense by the time their current license expires are automatically granted annual license extensions by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC).

In the past decade, FERC issued 80 relicenses that extended the authorization for hydroelectric projects to operate an additional 30 to 50 years. In the decade of the 2020s, 281 licenses, representing roughly 30 percent of the nation’s non-federal hydroelectric facilities, are set to expire. This represents a monumental explosion in required relicensing activity and makes timely action highly improbable.

The time, cost, and uncertainty involved in relicensing an existing hydropower facility are diametrically at odds with the urgency of addressing climate change and the upcoming wave of hydropower relicensing proceedings. They threaten the availability of the renewable energy provided by the existing hydropower fleet. Indeed, many hydropower industry asset owners are actively considering decommissioning a facility. These same uncertainties discourage development of new facilities and make their financing extremely difficult.

Critics of hydropower often stall and prolong the permitting process by pointing to dislocation of people for reservoirs, changes to original river flow, ecological disruption, and fish passage issues. We need to acknowledge that there often are ways to address these issues. Existing dams can have generation capability added or upgraded without changing river flow or additional ecological impact. Transmission lines connecting existing hydropower facilities to the grid already are in place. Pumped storage facilities require smaller reservoirs than traditional facilities. In fact, they can be built away from rivers, even in abandoned mine sites. Significant advances have been made in fish passage technology, including the introduction of turbines that pass fish unharmed.

We need to improve cooperation among FERC, tribes, and resource agencies, thereby streamlining the licensing process. One highly encouraging move in this regard was the establishment of the Uncommon Dialogue in 2018. It has connected more than 300 leaders and professionals representing a cross-section of hydropower interests from state and federal resource agencies, the Department of Energy, tribes, environmental and river conservation communities, the hydropower industry, academia, and national laboratories.

We additionally need to compel FERC and the other agencies involved in licensing to be more transparent and provide better documentation in support of conditions and prescriptions placed on hydropower licenses.

And it is critically important that there be strict deadlines in the licensing process. FERC currently lacks the authority to enforce deadlines. FERC, as lead agency, should be able to control the overall licensing process, and set and enforce reasonable deadlines.

It is high time to streamline and shorten the licensing process to open the floodgates for hydropower’s contributions in the age of climate change.

May 8, 2023